A Portfolio of Work

Reference Work

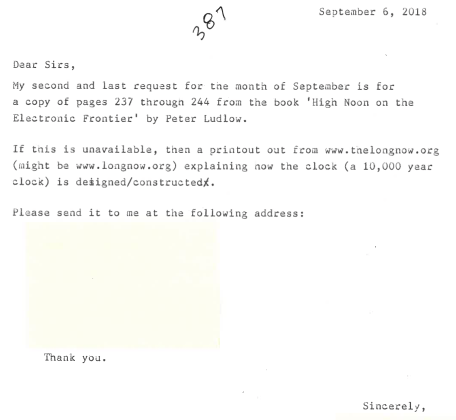

There are quite a few projects I've undertaken throughout my time in the GSLIS program that I'm proud of, but the following are some highlights that I will carry with me into future endeavors. My first semester in the program, as part of LSC 504, we worked with San Francisco Public Library answering reference questions for incarcerated people throughout the country as part of their mail in reference program. We would receive the letter and based upon the information requested from the individual, we'd evaluate sources, think about how to format them in a finite number of pages, and prioritize which information from a particular source was best suited to answer their particular question. Prisons have no internet access for inmates, and their library services and collections may be limited. This program not only answers general information inquiries, but it also helps incarcerated people prepare for life outside prison, which may look completely different with the advent of digital technologies for things like job seeking, skills on the job, and general communication from when they were first incarcerated. Snapshots of the letter I received and the letter I responded with are below. This work was incredibly meaningful to me; acknowledging that we live in a country with a racist and classist justice system that people profit from adds another layer to this work. It's the kind of social justice informed library service that I want to dedicate myself to no matter what kind of library job I eventually take.

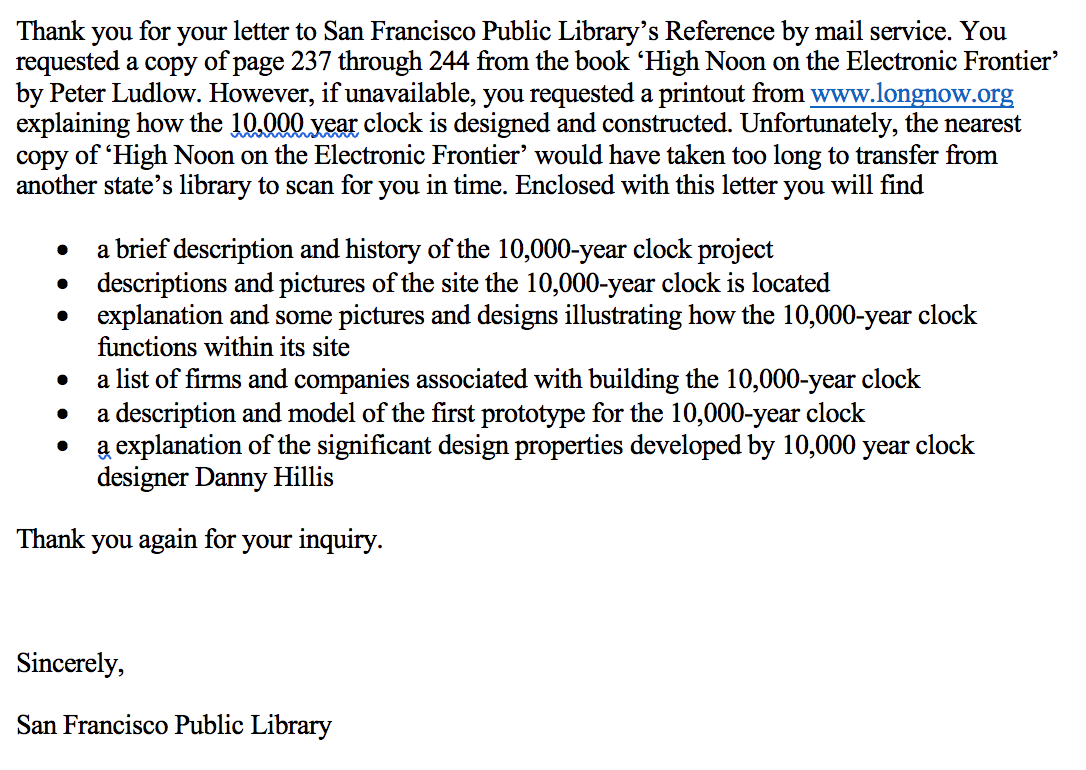

In the same class, I had to create a LibGuide, which is essentially a website where librarians build and compile resources for people based around a topical interest or need. This was my first experiment in web development and information architecture, though I wasn't yet thinking of it in those terms. In retrospect, this LibGuide provides so much information that it's probably overwhelming and difficult to utilize for the needs of most users. Much of what I've learned through the physical provision and layout of information from this course is that less is more. Users want convenient, practical pathways to meet their information needs. The physical layout of this LibGuide might be so sprawling and overwhelming that users may decide to go elsewhere for simpler, less time consuming answers. However, I'm still proud of the work I did utilizing a completely new interface to present a variety of information about such a broad and important topic. You can visit my LibGuide at What To Do Between Elections.

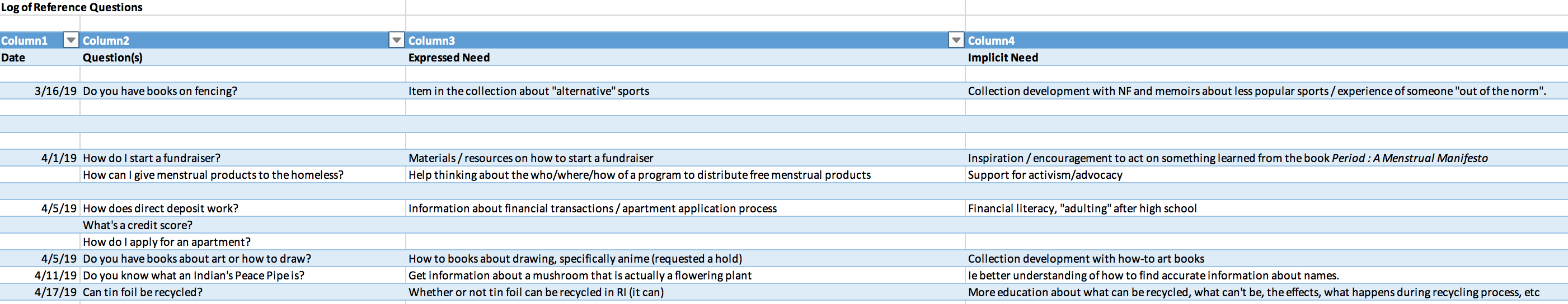

A final highlight from my reference work in the program actually came out of LSC 508, which focused on information science and digital technology. This course prompted us to ask questions about what the object of study in information science actually is. It asked sprawling philosophical questions like: what is information? How do users seek it, use it, and act upon it? And how can we use those understandings to better serve our population of users, no matter what kind of information professional we work as? These questions helped me make use of one of the digital tools we had to learn about--Microsoft Excel--to a practical applciation at my job at the time. I started to build a log on Excel as an effort to keep a physical record of questions our patrons asked; although it's somewhat impractical to take the time to log every single question we get asked in a day, I found the spreadsheet to be a great way to track questions that were in some way useful. Questions that sparked the information scientist part of my brain. Mostly, I made sure to document questions that were somewhat difficult to answer, or that indicated a current gap in our services. Those questions were often about topics that weren't well represented in our collection. But sometimes they were also notes about users' needs for services that could then be harnessed into programming offerings later. That's a way to ensure that we're building our services and collections around actual expressed needs of library users, tethering our decisions to data rather than conjecture, however well-informed it may be.

What I was really trying to track with the log was library users' needs for information, so that we could then address them later. Eventually, this could grow into a data analysis: we'd be able to track and plot the various needs users bring to us across different categories, like programming, collection development, community services, and more.

Original Cataloging

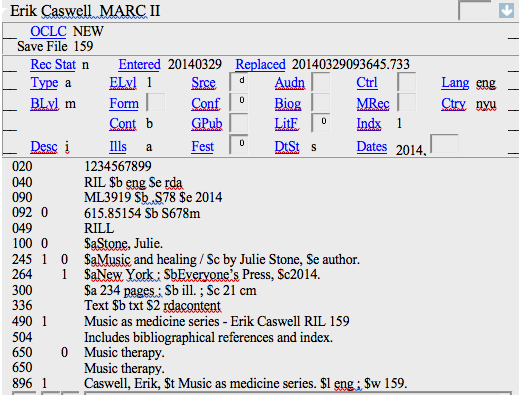

In the words of a friend who was looking at my MARC record when I was still in the drafting phase, "What is this WingDings I'm looking at right now?" LSC 505 on the Organization of Information helped show me exactly why the work of cataloging, keeping individual records of every material in a collection, and designing systems of storing and retrieving information is advanced professional work. Before this course, I had sort of taken the functionality of a library catalog for granted. What you realize when building a record for an item is just how much thought, work, and behind-the-scenes expertise goes into allowing you to search for items based on title, author, subject, and format. Every single one of those criterion reflects back to an individual field that someone somewhere had to enter in an office. Although much of the work of catalogers in small public libraries is done through copy cataloging, there is still a need for original cataloging, and metadata experts who allow users to navigate resources at their disposal. Admittedly, creating this record and understanding each of its various pieces by maneuvering through the highly technical language of standardized manuals was incredibly challenging for me. That's why I've included this sample MARC record as a piece of work I'm proud of. The single record you see below is a culmination of a whole semester's work and reading trying to understand the language of cataloging, and how concepts like authority control, standardized subject headings, and systems of classification function in libraries around the world.

Instruction & Programming

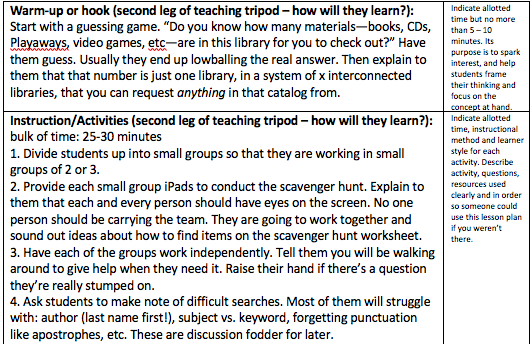

The final highlights I want to mention came out of my experiences primarily with LSC 527 about digital information literacy instruction. Part of a librarian's job is often about teaching, even if in a loose and informal way, as with public library programming. You don't necessarily have to center all of your "lessons" and programs in common core standards for learning outcomes. However, learning these things and drafting a formal lesson plan before you lead a class or program leads to much stronger results. Below is a draft of a lesson plan I made for that course, and I was actually able to implement it with a big group of middle schoolers who visited the library I worked at when I was a young adult associate in the teen space. The key to making an engaging lesson where people are actually interested in learning what you sought out to teach is to plan activities that are interactive, and dare I say, maybe even fun. I wound up teaching two groups of 30 sixth graders how to use the library catalog. But rather than just walk them through the catalog on a screen, I structured it as a sort of scavenger hunt. They had to navigate the catalog through trial and error, and we all regrouped at the end of the lesson to discuss what they'd learned, which pieces of the scavenger hunt were the most difficult to locate, and then they named one item they wanted to find and stated which library in the OSL system it could be found.

The final highlights I want to mention came out of my experiences primarily with LSC 527 about digital information literacy instruction. Part of a librarian's job is often about teaching, even if in a loose and informal way, as with public library programming. You don't necessarily have to center all of your "lessons" and programs in common core standards for learning outcomes. However, learning these things and drafting a formal lesson plan before you lead a class or program leads to much stronger results. Below is a draft of a lesson plan I made for that course, and I was actually able to implement it with a big group of middle schoolers who visited the library I worked at when I was a young adult associate in the teen space. The key to making an engaging lesson where people are actually interested in learning what you sought out to teach is to plan activities that are interactive, and dare I say, maybe even fun. I wound up teaching two groups of 30 sixth graders how to use the library catalog. But rather than just walk them through the catalog on a screen, I structured it as a sort of scavenger hunt. They had to navigate the catalog through trial and error, and we all regrouped at the end of the lesson to discuss what they'd learned, which pieces of the scavenger hunt were the most difficult to locate, and then they named one item they wanted to find and stated which library in the OSL system it could be found.

Lastly, although this wasn't a direct assignment that came out of my GSLIS work, our discussions about programming, research about what libraries have to offer their users, and the course I mentioned in the previous exmaple absolutely helped me facilitate a writing workshop offered for adults at the library. One of the things I quickly realized when starting the workshop was that it couldn't really run like a class. People weren't going to keep showing up and participate if one person was always running the show, so to speak. It's not like they were receiving course credit for completing assignments, prompts, and readings they had no part in creating themselves. As I learned more about how successful library programs run, I restructured the group so that basically a new person each week was responsible for what we did. Someone elected a prompt for us all to prepare, and someone would bring in writing of their own for group feedback. As the group's numbers grew, we were able to tackle more ambitious projects. In a little less than two years from the time I started the group and struggled to get more than a couple of people to show up, this group transformed into an actual, collaborative library program and we were able to put together an anthology of work for sale to show the community what it is we've been doing on Saturday mornings. If I hadn't drawn from GSLIS curriculum and research to rethink how a writing workshop operates in the context of public library space rather than the more formal, teacher-student model of a classroom, I think a project like this wouldn't have ever gone anywhere. That's why I've included it in this portfolio of GSLIS work.